Maya MERCER

Introduction

Maya Mercer is a Franco-American artist. Daughter of radical English dramatist, playwright, and screenwriter David Mercer, Maya grew up between London, Paris, and Los Angeles. Self-taught as a visual artist, Mercer has always lived in a narrative world, experiencing “life as theater” from early childhood. She calls herself a regionalist “photocinema” artist. Mercer now lives and works in Northern Carolina where she directs mostly teenagers in visual stories inspired by the social conditions of the rural American Far West. Her work has been shown in galleries, museum exhibitions and art fairs throughout North America and Europe.

"Mercer has become an adopted daughter of the Wild West. Living as she does in north carolina, that vast and varied state, a country within a country, has its grip on her entire consciousness. She finds it a First World within a First World — and a Third World within a Third World as well.

Mercer's subjects are young, beautiful, tragic and playful, and strangely removed from time even as they reflect contemporary stresses and historic memories. While her art echoes the decadence of late-19th century precursors, however, it also looks ahead to a new, perilous age of sensuality, confusion, and encroaching dystopia. In this regard Maya Mercer is less hedonist than oracle, less Salome than Cassandra. Her work is no indulgence; it is a warning.”

Peter Frank

Biography

Solo exhibitions

2019

- The Parochial Segments, en collaboration avec Paris Photo, Silencio, Paris, FR

2010

- Ladykillers, Stephen Cohen Gallery, Los Angeles, USA

Group exhibitions

2020

- Photo Basel, first online edition, with baudoin lebon

- Féminin, Galerie Agathe Gaillard, Paris, FR

- 7000 Magazine, Paris, FR

- L'Antichambre acte 2, baudoin lebon, Paris, FR

2017

- Transangeles, Neuer Kunstverein Museum, Aschaffenburg, DE

2016

- Transangeles, Chabot Museum, Rotterdam, NL

2014

- Transangeles, Wilhelm-Morgner-Haus, Soest, DE

2012

- 99% Exhibition, Ace Museum, Los Angeles, USA

2010

- Photo L.A., Stephen Cohen Gallery, Los Angeles, USA

2009

- Photo L.A., Jail Gallery, Los Angeles, USA

2008

- Photo LA, Jail Gallery, Los Angeles, USA

- ART Chicago, Jail Gallery, Los Angeles, USA

- Scope Art Fair, Jail Gallery, Basel, CH

texts

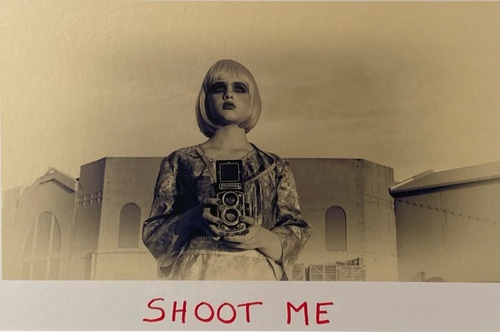

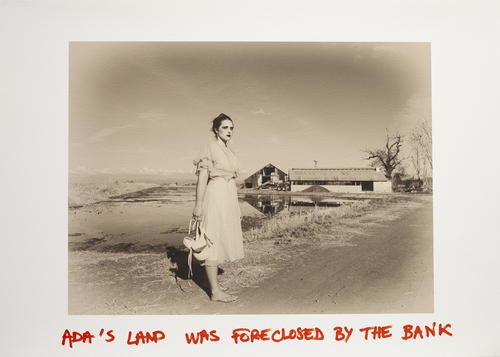

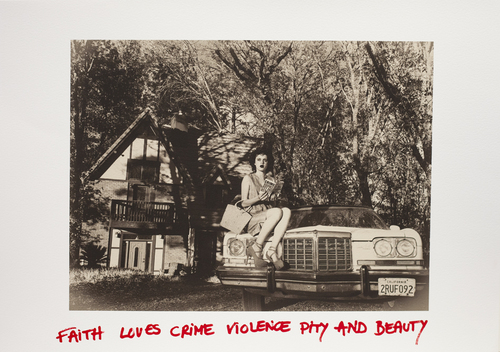

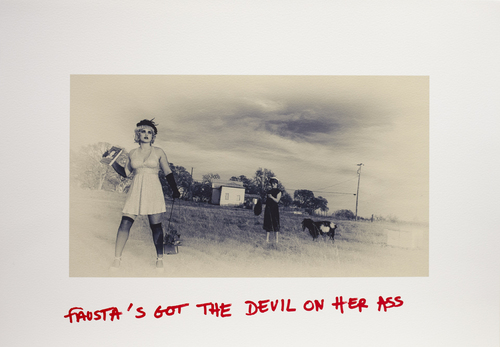

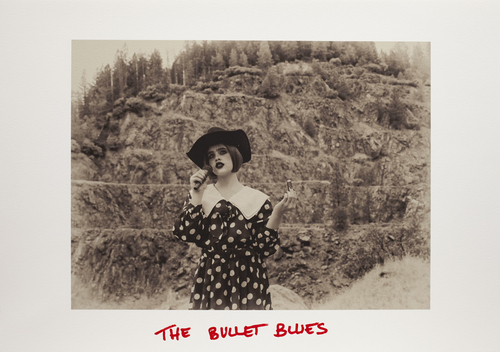

THE WESTEND GIRLS

Maya Mercer has become an adopted daughter of the Wild West. The United States has its grip on Mercer's entire consciousness, living deep in the interior of that vast and varied state - California- a country within a country, a First World within a First World.

But it is a Third World within a Third World as well. The rigors of 19th- century life were never cleansed from America's body, much less its soul. It has never stopped fighting its Civil War. It has always regarded itself as some sort of Darwinian fight club, a place where people come not to live but to survive, to pursue liberty at the expense of happiness.

The indiscreet underbelly of American life, its vast sea of proletarian anguish, has now erupted at its surface. The comic manifestation of this in the prosaic language of politics and entertainment reigns in Washington. But Mercer seeks the tragic manifestation of the American fever dream, the small-town, small-bore spirit whose hope against hope and despair upon despair wash over the forgotten like brackish pond water.

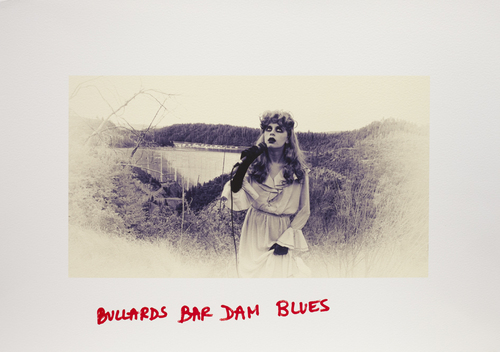

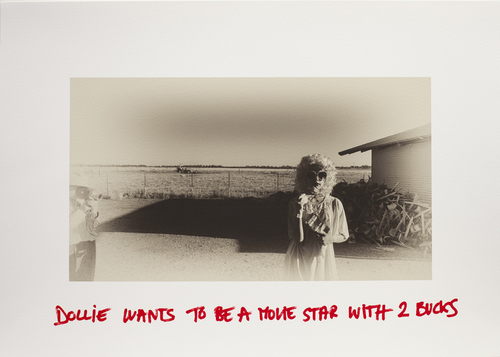

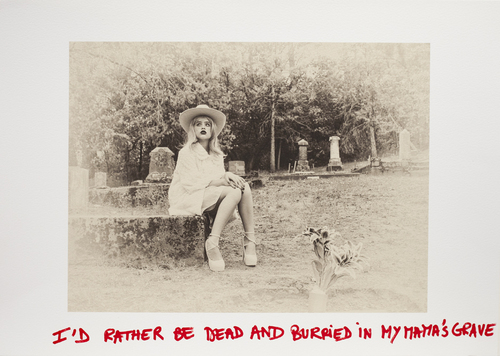

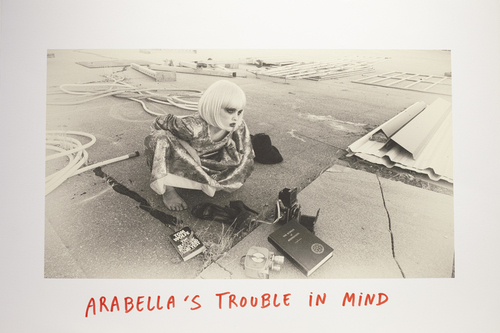

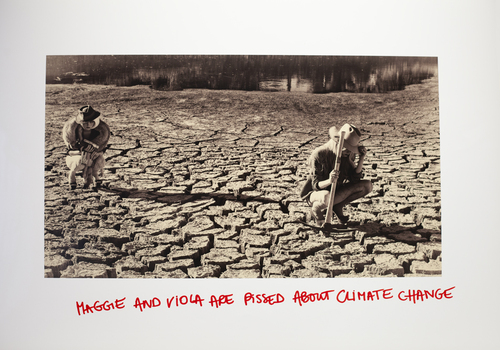

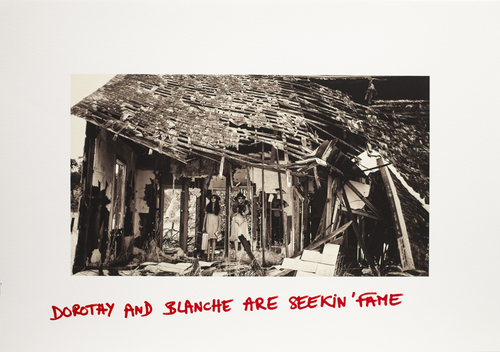

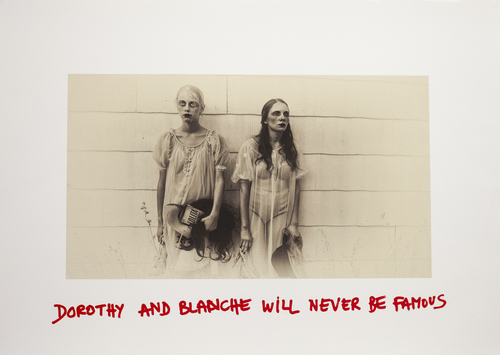

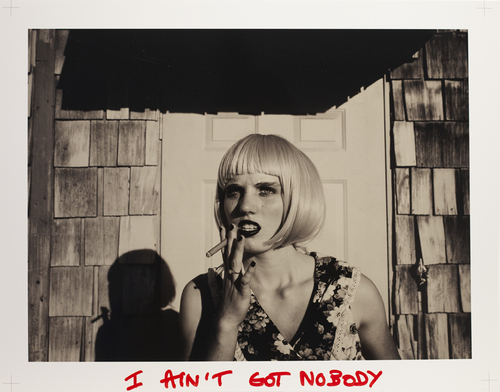

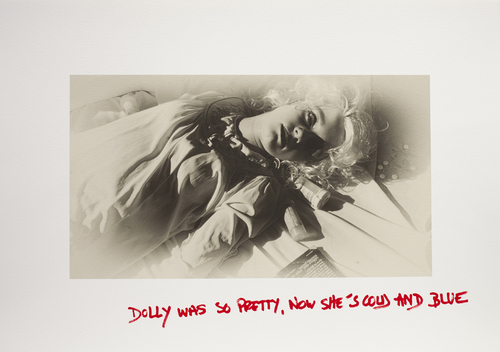

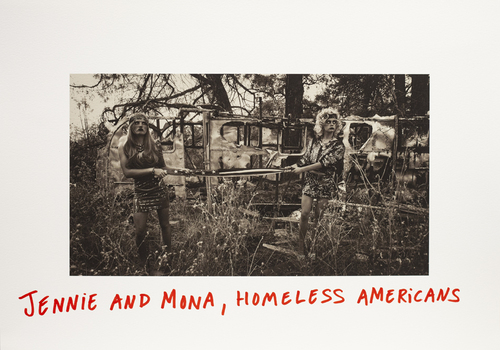

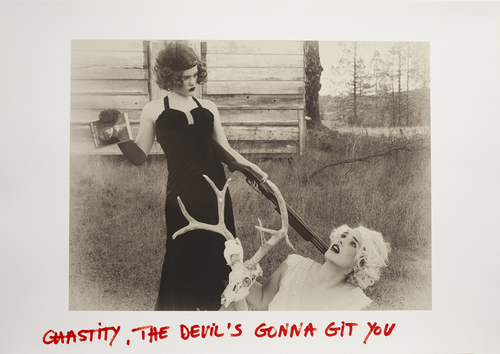

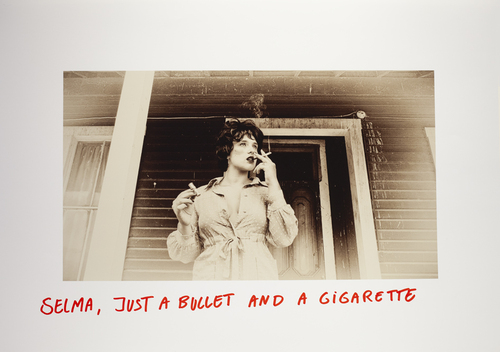

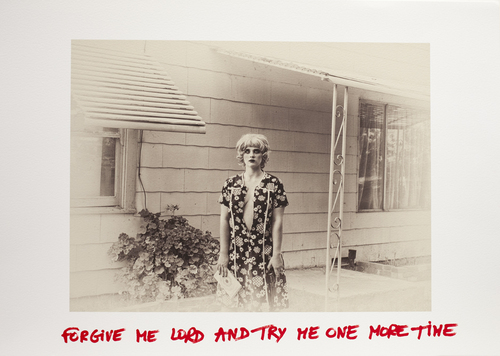

“The Westend Girls” finds poetry in the meanness of life. Mercer has her local “bad girls” enact so many different little stanzas, any one of them a dramatic moment that their grandmothers could have lived, or that they might go on to live. The images in this series are ballads to boldness and to futility, making heroines of their adolescents and/or of the women they play. Their schemes are not grand, but even then they can't be achieved; there is an inertia at the heart of this existence that keeps these girls rooted to their blasted locale. There is no escape because there is nowhere they can imagine going to.

Too bad, because, as Mercer's photography reveals, these young women are ambitious, feisty, and formidable, sisters at heart even when not at core. Their ennui never dispels their vision, but never lets it emerge, either. Mercer has had to dream for them, but she has not imposed such dreaming on them so much as coaxed it out of them. It is a Hollywood- inflected dream, but not a Hollywood dream: the setting is coarse, the story arc breaks in many places, the ending isn't happy. It is laced with skepticism, but it allows the girls their lingering innocence, so it is almost free of cynicism.

One foot in fantasy, one foot in reality -- and constantly unsure as to which is which -- “The Westend Girls” surveys the landscape of unfulfilled promises that is latter-day America.

– Peter Frank, Los Angeles, April 2018

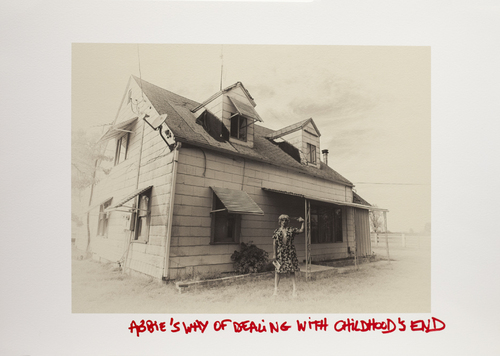

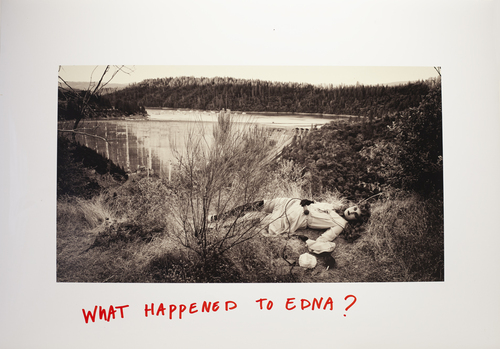

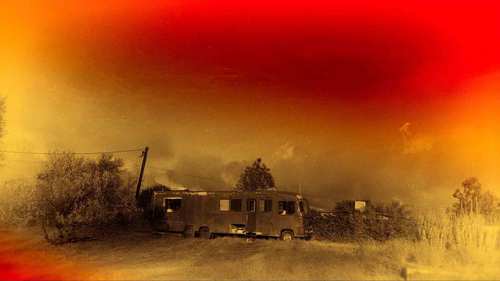

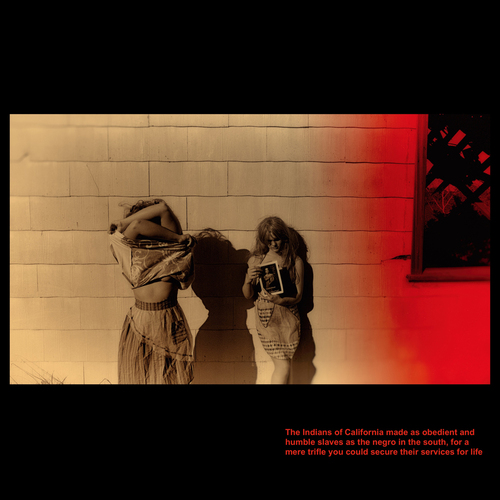

PAROCHIAL SEGMENTS

PAROCHIAL SEGMENTS, despite its implicitly constricting title, opens up the sequence of photographs Maya Mercer has been compiling of her Northern California neighborhood and neighbors. The new series shifts emphasis away from the inwardly-turned gaze of CULT and the brittle sociology of WESTEND GIRLS to a seemingly picturesque comprehension of the poor Sierra foothills community on which Mercer concentrates. But the landscape, however grand, however much breadth it may afford its inhabitants, is a prison more than a free field. The distant mountains and the nearby water do not promise release; they promise entrapment. And, as Mercer's photos whisper, they threaten devastation.

The children in these Parochial Segments, slouching towards adolescence, are caught mid- chrysalis, abandoning their innocence and waking to a realization that home is not simply their refuge, but is their fate. They — or the people who came here and made them — settled this forsaken corner of America as if landing on Mars. They found themselves safe here, so they are safe, they think, only here. Their lives and their surroundings are degraded, but they have convinced themselves — and these, their children — that the outside world is worse. This was once “Indian country,” inhabited by Native American peoples who roamed as they could and needed to. But Mercer's subjects are the descendants of Caucasians who made their way here not 100 years ago, fleeing the disruption of their Great Plains farming. These “Okies,” about whom John Steinbeck wrote so sensitively, flooded California in waves reminiscent of today's migrations, and encountered the same resistance, prejudice, and cruelty — from their fellow Americans, their fellow white people, who disdained them as poor filth. Theirs was not a race conflict, but a class conflict. And still is.

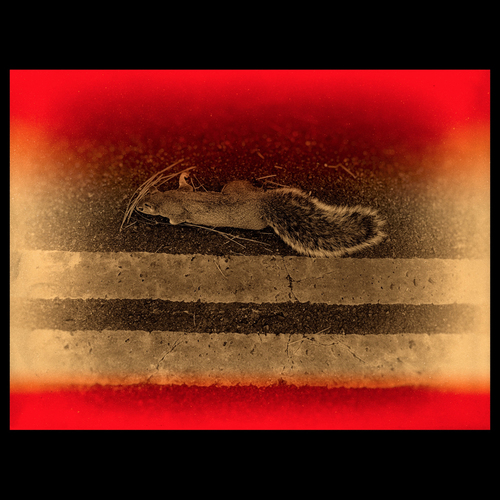

These children have not inherited the land, they have inherited the fearful, ingrown mindset of those who were able to stay but not quite able to sustain themselves, and had nowhere else to go. And now these children will face a 21st-century version of rejection and isolation, as even the land will change beneath their feet. In the great Anthropocene die-off, they will be the first to go. Or will they be the last?

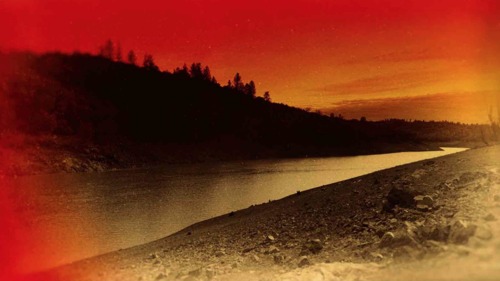

Refusing simply to document poverty, Mercer practically paints a picture of the doomed, not simply capturing their aloneness beneath a big, empty sky but infecting her images with what can seem a veil of blood, a persistent red saturation that augurs sickness and death without necessarily conjuring violence. This red can be naturally found in the atmosphere, especially at sunset; but in the intensity it takes on in Mercer's lens it signals a poisoned ecology as well as the catastrophic immobility of the next human generation. The Grapes of Wrath turns, seamlessly, into Children of the Damned.

Mercer, born to a family in cinema, is not afraid to work melodramatically. Indeed, by fantasizing apocalypse around these orphans of the American outback, she helps liberate them in a sense from their dismal quotidian existence. She provides them clothing and devices, for her photographs or for real, to begin elevating them; but, finally, she can uproot them only by articulating the calamities waiting to descend on them from the mountaintops and down the rivers. Spectacular extinction will cut short inglorious life.

Doubtless, these damned children would rather survive. So would we all. But they have less to lose — and, living as close to the land as they do, they may prove more resourceful than we are. Wouldn't it be just if Mercer's little colony of the prepubescent becomes an oasis in the midst of global environmental collapse?

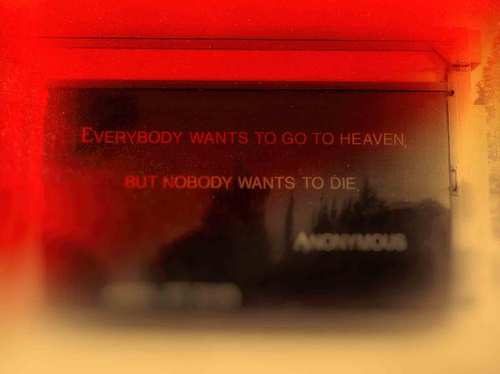

The term “parochial,” Maya Mercer explains, was used by early Christians to denote their colonies. The Greek-sourced word invokes temporality, and, indeed, it was used to infer that the Christians' permanent home was heaven. No doubt some of these young people are being raised as devout Christians and believe fervently in the Next Life and the Second Coming. They hold on dearly to their parochialism, as that's all they believe they have — or need, since heaven awaits. But their journey to that ultimate life, Mercer suggests, will not be abetted by bad habits and poor diet, but by the nature around them, the nature they depend on simply to be there the next day, turning monstrous. “Parochial Segments” is not only about the parishioners, but about what awaits them.

– Peter Frank, Los Angeles, July 2019